El sucio secreto de Raqqa [ENG]

por Jakeukalane a bbc.co.uk 20:21 publicado: 02:05

La BBC ha destapado los detalles de un acuerdo secreto para dejar marchar a cientos de combatientes (incluidos militantes extranjeros) y sus familias de Raqqa (Siria) a cambio de liberar a rehenes, bajo la mirada de la coalición liderada por EEUU e Inglaterra, y las fuerzas lideradas por los kurdos que ahora controlan la ciudad.

por Jakeukalane a bbc.co.uk 20:21 publicado: 02:05

La BBC ha destapado los detalles de un acuerdo secreto para dejar marchar a cientos de combatientes (incluidos militantes extranjeros) y sus familias de Raqqa (Siria) a cambio de liberar a rehenes, bajo la mirada de la coalición liderada por EEUU e Inglaterra, y las fuerzas lideradas por los kurdos que ahora controlan la ciudad.

por Jakeukalane a bbc.co.uk 20:21 publicado: 02:05

por Jakeukalane a bbc.co.uk 20:21 publicado: 02:05El sucio secreto de Raqqa

Por Quentin Sommerville y Riam Dalati

La BBC ha revelado detalles de un acuerdo secreto que permite que cientos de combatientes de IS y sus familias escapen de Raqqa, bajo la mirada de la coalición liderada por Estados Unidos e Inglaterra y las fuerzas lideradas por los kurdos que controlan la ciudad.

Un convoy incluyó a algunos de los miembros más notorios de IS y, a pesar de las afirmaciones, docenas de combatientes extranjeros. Algunos de ellos se han extendido por toda Siria, incluso llegando hasta Turquía.

El conductor del camión, Abu Fawzi, pensó que iba a ser solo otro trabajo.

Él conduce un vehículo de 18 ruedas a través de algunos de los territorios más peligrosos en el norte de Siria. Puentes bombardeados, arena profunda del desierto, incluso fuerzas del gobierno y los llamados combatientes del Estado Islámico no se interponen en el camino de una entrega.

Pero esta vez, su carga sería carga humana.

Las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (SDF), una alianza de combatientes kurdos y árabes opuestos a IS, querían que dirigiera un convoy que llevaría a cientos de familias desplazadas por la lucha de la ciudad de Tabqa en el río Eufrates a un campamento más al norte.

El trabajo tomaría seis horas como máximo, o al menos eso es lo que le dijeron.

Pero cuando él y sus compañeros conductores reunieron su convoy temprano el 12 de octubre, se dieron cuenta de que les habían mentido.

En cambio, tomaría tres días de manejo duro, llevando un cargamento mortal: cientos de combatientes de IS, sus familias y toneladas de armas y municiones.

A Abu Fawzi y docenas de otros conductores se les prometieron miles de dólares por la tarea, pero debía permanecer en secreto.

El acuerdo para permitir que los combatientes del EI escaparan de Raqqa, capital de facto de su autoproclamado califato, había sido organizado por funcionarios locales.

Llegó después de cuatro meses de combates que dejaron a la ciudad borrada y casi desprovista de gente. Perjudicaría vidas y llevaría la lucha a su fin. Las vidas de los combatientes árabes, kurdos y otros que se oponen a IS se salvarían.

Pero también permitió a muchos cientos de combatientes de IS escapar de la ciudad. En ese momento, ni la coalición encabezada por Estados Unidos ni los británicos, ni el SDF, que respalda, querían admitir su parte.

¿El pacto, que era el secreto sucio de Raqqa, desató una amenaza para el mundo exterior, que ha permitido a los militantes extenderse por Siria y más allá?

Grandes dolores fueron tomados para esconderlo del mundo. Pero la BBC ha hablado con docenas de personas que estaban en el convoy u observado, y con los hombres que negociaron el trato.

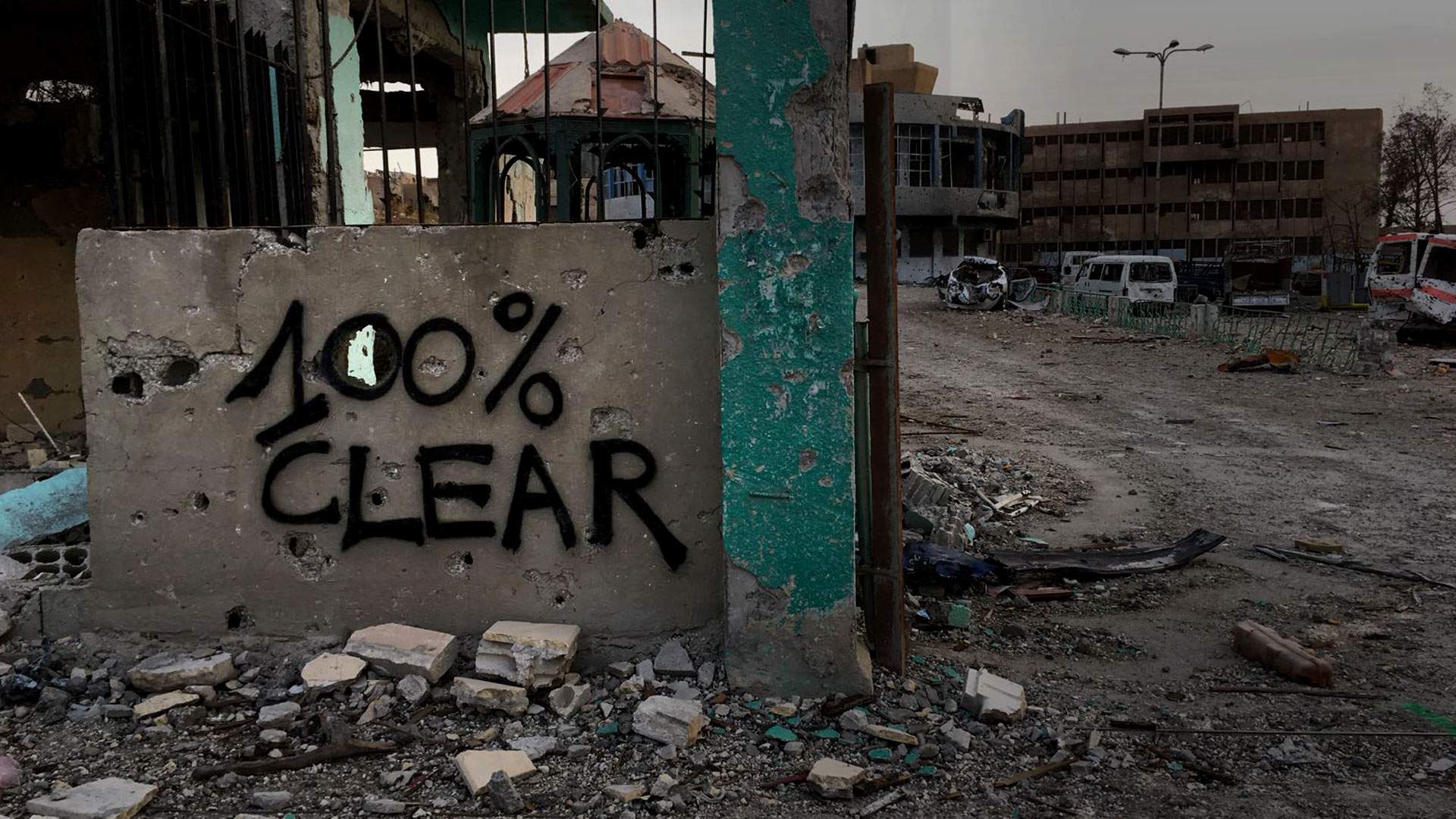

Fuera de la ciudad

En un patio grasiento en Tabqa, debajo de una palmera datilera, tres niños están ocupados en el trabajo reconstruyendo un camión de motor. Están cubiertos de aceite de motor. Su cabello, negro y grasiento, se eriza.

Cerca de ellos hay un grupo de conductores. Abu Fawzi está en el centro, conspicuo en su chaqueta roja brillante. Coincide con el color de su amado de 18 ruedas. Él es claramente el líder, rápido para ofrecer té y cigarrillos. Al principio dice que no quiere hablar, pero pronto cambia de opinión.

Él y el resto de los conductores están enojados. Han pasado semanas desde que arriesgaron sus vidas por un viaje que arruinó los motores y quebraron los ejes, pero aún no han sido pagados. Fue un viaje al infierno y de regreso, dice.

Uno de los controladores indica la ruta del convoy

Uno de los controladores indica la ruta del convoy

"Tuvimos miedo desde el momento en que ingresamos a Raqqa", dice. "Se suponía que íbamos a ir con el SDF, pero fuimos solos. Tan pronto como entramos, vimos a combatientes de IS con sus armas y sus cinturones de suicidio puestos.

Atraparon nuestros camiones con trampas explosivas. Si algo saliera mal en el trato, bombardearían todo el convoy. Incluso sus hijos y mujeres tenían cinturones de suicidio ".

El SDF liderado por los kurdos limpió a Raqqa de los medios. El escape del Estado Islámico de su base no sería televisado.

Públicamente, el SDF dijo que solo unas pocas docenas de combatientes habían podido irse, todos locales.

Pero un conductor de camión nos dice que eso no es cierto.

Eliminamos a unas 4.000 personas, incluidas mujeres y niños, nuestro vehículo y sus vehículos combinados.

Cuando entramos en Raqqa, pensamos que había 200 personas para recoger. En mi vehículo solo, tomé 112 personas ".

Otro conductor dice que el convoy tenía entre seis y siete kilómetros de largo. Incluyó casi 50 camiones, 13 autobuses y más de 100 vehículos propios del grupo Estado Islámico.

Los luchadores de IS, con el rostro cubierto, se sentaron desafiantes encima de algunos de los vehículos.

La filmación secretamente filmada y transmitida muestra camiones que remolcan remolques repletos de hombres armados. A pesar de un acuerdo para llevar solo armas personales, los combatientes de IS tomaron todo lo que pudieron transportar.

Diez camiones fueron cargados con armas y municiones.

Los conductores señalan que se está trabajando en un camión blanco en la esquina del patio. "Su eje se rompió debido al peso de la munición", dice Abu Fawzi.

Esto no fue tanto una evacuación, sino el éxodo del llamado Estado Islámico.

El SDF no quería que la retirada de Raqqa pareciera un escape a la victoria. No se permitiría que se volaran banderas o pancartas desde el convoy cuando saliera de la ciudad, según lo estipulado.

También se entendió que no paraSe espera que los extranjeros salgan vivos de Raqqa.

En mayo, el secretario de Defensa de los EE. UU., James Mattis, describió la lucha contra IS como una guerra de "aniquilación". Nuestra intención es que los combatientes extranjeros no sobrevivan a la lucha por regresar al norte de África. , a Europa, a América, a Asia, a África.

No les vamos a permitir que lo hagan ", dijo en la televisión estadounidense.

Pero los combatientes extranjeros, los que no son de Siria e Irak, también pudieron unirse al convoy, de acuerdo con los conductores.

Una explica: había una gran cantidad de extranjeros. Francia, Turquía, Azerbaiyán, Pakistán, Yemen, Arabia Saudita, China, Túnez, Egipto ... "Otros conductores aportaron nombres de diferentes nacionalidades. A la luz de la investigación de la BBC, la coalición ahora admite la parte que jugó en el acuerdo. .

Unos 250 combatientes de IS fueron autorizados a abandonar Raqqa, con 3.500 de sus familiares.

"No queríamos que nadie se fuera", dice Col Ryan Dillon, portavoz de Operation Inherent Resolve, la coalición occidental contra IS.

"Pero esto va a el corazón de nuestra estrategia, 'por, con y a través' de los líderes locales sobre el terreno.

Todo se reduce a los sirios: son ellos los que luchan y mueren, toman decisiones sobre las operaciones ", dice. Mientras un oficial occidental estuvo presente para las negociaciones, no tomaron una" parte activa "en las discusiones. .

Col Dillon mantiene, sin embargo, que solo cuatro combatientes extranjeros se fueron y ahora están bajo custodia de SDF. Los miembros de la familia se preparan para irse.

Los miembros de la familia se preparan para irse.

Al salir de la ciudad, el convoy pasaría por los campos de algodón y trigo bien irrigados. de Raqqa. Los pequeños pueblos dieron paso al desierto. El convoy salió de la carretera principal y tomó pistas por el desierto. A los camiones les resultaba difícil, pero era mucho más difícil para los hombres detrás del volante.

Un amigo de Abu Fawzi subió la manga de su túnica. Debajo, hay quemaduras en su piel. "Miren lo que hicieron aquí", dice.

Según Abu Fawzi, había tres o cuatro extranjeros con cada conductor. Le pegarían y le pondrían nombres, como "infiel" o "cerdo". Podrían haber ayudado a los luchadores a escapar, pero los conductores árabes fueron abusados durante toda la ruta, dicen.

Y amenazado. "Dijeron: 'Avísenos cuando reconstruyan Raqqa, volveremos'", dice Abu Fawzi. "Eran desafiantes y no les importó. Nos acusaron de expulsarlos de Raqqa. "Una mujer combatiente extranjera lo amenazó con su AK-47.

En el desierto, el escolta Mahmoud no se deja intimidar por nada. Eran aproximadamente las cuatro de la tarde cuando un convoy de SDF pasó por su pueblo. , Shanine, ya todos se les dijo que fueran adentro. "Estábamos aquí y un vehículo de SDF se detuvo para decir que había un acuerdo de tregua entre ellos y el SI", dice.

"Querían que despejáramos el área". No es un fanático de IS, pero no podía perder una oportunidad comercial, incluso si algunos de los 4.000 clientes que conducían por su pueblo estaban armados hasta los dientes.

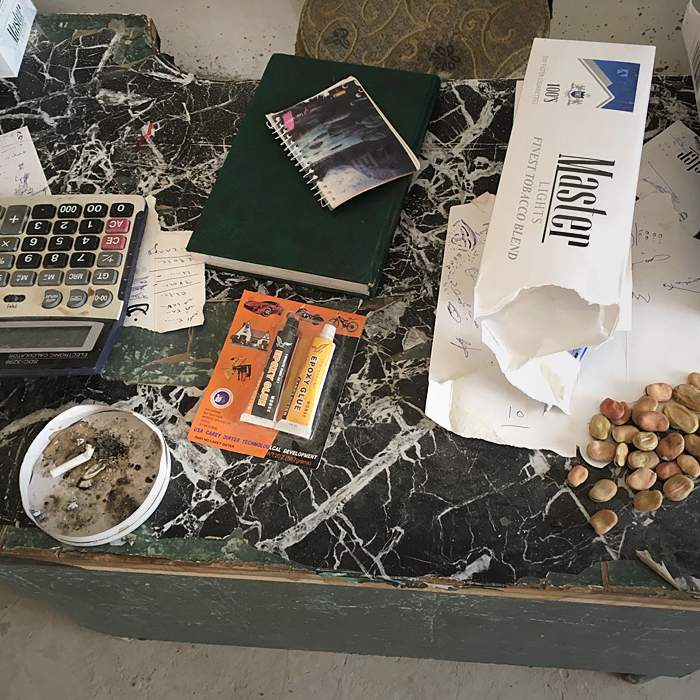

La tienda de Mahmoud

Un pequeño puente en la aldea creó un cuello de botella por lo que los combatientes de IS salieron y fueron de compras.

Después de meses de luchar y refugiarse en los búnkeres, estaban pálidos y hambrientos. Registraron en su tienda y, dice, limpiaron sus estantes.

"Un luchador tunecino tuerto me dijo que temiera a Dios", dice.

"Con voz muy tranquila, me preguntó por qué me había afeitado.

Dijo que regresarían y harían cumplir la Sharia una vez más. Le dije que no tenemos ningún problema con las leyes de Sharia.

Todos somos musulmanes ".

Fideos, galletas y bocadillos instantáneos: compraron todo lo que pudieron conseguir. Dejaron sus armas fuera de la tienda.

El único problema que tuvo fue cuando tres de los luchadores divisaron algunos cigarrillos -en contrabando en sus ojos- y rompieron las cajas.

"No se apropiaron de nada, nada en absoluto", dice.

"Solo tres de ellos fueron deshonestos.

Otros luchadores de la IS incluso los regañaron. "

Dice que IS fue pagado por lo que tomaron".

Aspiraron por la tienda. Me sentí abrumado por sus números. Muchos me pidieron precios, pero no pude responderlos porque estaba ocupado atendiendo a otras personas.

Así que me dejaron dinero en mi escritorio sin que yo lo preguntara ". A pesar de los abusos que sufrieron, los camioneros estuvieron de acuerdo: cuando se trataba de dinero, IS liquidaba sus cuentas.

Es posible que haya sido un psicópata homicida, pero siempre es correcto con el dinero ". Afirma Abu Fawzi con una sonrisa.

En el norte de la aldea, es un paisaje diferente. Un tractor solitario ara un campo, enviando una nube de polvo y arena al aire que se puede ver por millas. Hay menos pueblos, y es aquí donde el convoy trató de desaparecer.

En la pequeña aldea de Muhanad, la gente huyó cuando el convoy se acercó, temiendo por sus hogares y sus vidas.

Pero de repente, los vehículos giraron a la derecha, dejando la carretera principal para un pista del desierto.

"Dos Humvees estaban liderando el convoy por delante", dice Muhanad. "Lo estaban organizando y no dejarían que nadie los pasara". Cuando el convoy desapareció en la bruma del desierto, Muhanad no sintió un alivio inmediato.

Casi todas las personas con las que hablamos dicen que IS amenaza con regresar, y que sus combatientes pasan un dedo por el cuello

" Hemos estado viviendo en estado de terror durante los últimos cuatro o cinco años", dice Muhanad.

Nos tomará un tiempo deshacernos de ese miedo psicológico. Creemos que pueden regresar por nosotros o enviarán agentes durmientes.

Todavía no estamos seguros de que se hayan ido para siempre ".

A lo largo de la ruta, muchas personas con las que hablamos dijeron que escucharon aviones de la coalición, a veces aviones no tripulados, siguiendo al convoy.

Desde la cabina de su camión, Abu Fawzi vio como una coalición el avión de guerra voló sobre sus cabezas, dejando caer bengalas de iluminación que iluminaron el convoy y la carretera.

Cuando el último del convoy estaba a punto de cruzar, un avión estadounidense voló muy bajo y desplegó bengalas para iluminar el área. Los combatientes de IS se sacuden el pantalón ".

La coalición ahora confirma que, aunque no tenía personal en el terreno, monitoreaba el convoy desde el aire. Presentaba el último punto de control SDF, dentro del territorio de IS, una aldea entre Markada y Al-Souwar. Abu Fawzi llegó a su destino.

Su camión estaba lleno de municiones y los cazas de la IS lo querían escondido.

Cuando finalmente regresó a un lugar seguro, la SDF le preguntó dónde había tirado la mercancía.

"Les mostramos la ubicación en el mapa y él lo marcó el tío Trump puede bombardearlo más tarde ", dice.

La libertad de Raqqa se compró con sangre, sacrificio y compromiso. El acuerdo liberó a sus civiles atrapados y terminó la lucha por la ciudad. Ninguna fuerza SDF tendría que morir asaltando el último escondite de IS.

Pero IS no permaneció por mucho tiempo. Liberados de Raqqa, donde fueron rodeados, algunos de los miembros más buscados del grupo se han extendido a lo largo y ancho de Siria y más allá.

Los contrabandistas Los hombres que cortan vallas, trepan muros y corren por los túneles de Siria informan un gran aumento en personas que huyen El colapso del califato es bueno para los negocios.

"En las últimas semanas, hemos tenido muchas familias que dejan Raqqa y quieren irse a Turquía. Solo esta semana, supervisé personalmente el contrabando de 20 familias ", dice Imad, un contrabandista en la frontera entre Turquía y Siria."

La mayoría eran extranjeros, pero también había sirios ".

Ahora cobra $ 600 (£ 460) por persona y un mínimo de $ 1,500 para una familia. En este negocio, los clientes no aceptan amablemente las consultas. Pero Imad dice que ha tenido "franceses, europeos, chechenos, uzbekos".

"Algunos estaban hablando en francés, otros en inglés, otros en algún idioma extranjero", dice.

Walid, otro contrabandista en otro tramo de la frontera turca, le dice la misma historia. "Tuvimos un influjo de familias en las últimas semanas", dice.

"Hubo algunas familias grandes cruzando. Nuestro trabajo es pasarlos de contrabando. Hemos tenido muchas familias extranjeras que usan nuestros servicios.

"A medida que Turquía ha aumentado la seguridad fronteriza, el trabajo se ha vuelto más difícil.

En algunas áreas usamos escaleras, en otros cruzamos un río, en otras áreas re usando un camino empinado montañoso. Es una situación miserable ". Sin embargo, Walid dice que es una situación diferente para las figuras senior de IS." Esos extranjeros altamente ubicados tienen sus propias redes de contrabandistas. Usualmente son las mismas personas quienes organizaron su acceso a Siria. Se coordinan entre sí.

"El contrabando no funcionó para todos. Abu Musab Huthaifa fue una de las figuras más notorias de Raqqa.

El jefe de inteligencia del EI se encontraba en el convoy fuera de la ciudad el 12 de octubre. Pero ahora está tras las rejas, y su historia refleja los últimos días del derrumbe del califato.

El Estado islámico nunca negocia. Incomprometido, asesino: este es un enemigo que juega con un conjunto diferente de reglas.

Al menos así es como va el mito. Abu Mus'abAbu Mus'ab Pero en Raqqa, no se comportó de manera diferente a cualquier otro lado perdedor.

Arrinconados, exhaustos y temerosos por sus familias, los combatientes del EI fueron bombardeados a la mesa de negociaciones el 10 de octubre.

"Los ataques aéreos nos presionan durante casi 10 horas. Mataron a unas 500 o 600 personas, combatientes y familias ", dice Abu Musab Huthaifa. El ataque aéreo de la coalición que golpeó un barrio de Raqqa el 11 de octubre muestra una catástrofe humana detrás de las líneas enemigas.

En medio de los gritos de las mujeres y los niños, existe un caos entre los luchadores de IS. Las bombas parecen especialmente poderosas, especialmente efectivas.

Los activistas afirman que un edificio que albergaba a 35 mujeres y niños fue destruido. Fue suficiente para romper su resistencia.

Contiene material angustiante "Después de 10 horas, las negociaciones comenzaron de nuevo. Aquellos que inicialmente rechazaron la tregua cambiaron de opinión. Y así nos fuimos de Raqqa ", dice Abu Musab. Hubo tres intentos previos de negociar un acuerdo de paz.

Un equipo de cuatro personas, incluidos los funcionarios locales de Raqqa, ahora dirigió las conversaciones.

Un alma valiente cruzaría las primeras líneas de su motocicleta transmitiendo mensajes.

"Solo íbamos a salir con nuestras armas personales y dejar atrás todas las armas pesadas. Pero no teníamos armas pesadas de todos modos ", dice Abu Musab. Ahora en la cárcel en la frontera entre Turquía y Siria, ha revelado detalles de lo que sucedió con el convoy cuando llegó sano y salvo al territorio de Israel.

Dice que el convoy fue a el campo del este de Siria, no lejos de la frontera"El intento de fuga de Abu Musab sirve como advertencia a Occidente de la amenaza de los liberados de Raqqa.

¿Cómo podría escapar uno de los jefes del EI más notorios a través del territorio enemigo y casi evadir la captura?".

Me quedé con un grupo que se propuso hacer su camino a Turquía ", dice Abu Musab.

Los miembros del Estado islámico eran queridos por todos los que estaban fuera del área de control del grupo; eso significaba que esta pequeña reunión tenía que atravesar franjas de territorio hostil. "Contratamos a un contrabandista para que nos sacara de las áreas controladas por SDF", dice Abu Musab. Al principio todo salió bien. Pero los contrabandistas son un grupo poco confiable.

"Nos abandonó a mitad de camino. Nos dejaron a nosotros mismos en medio de las áreas SDF. A partir de ese momento, nos separamos y fue todo hombre para él ", dice Abu Musab. Podría haber llegado a un lugar seguro si hubiera pagado a la persona adecuada o tal vez tomado una ruta diferente.

El otro camino es hacia Idlib, a al oeste de Raqqa. Innumerables luchadores de IS y sus familias han encontrado un refugio allí. Los extranjeros también lo logran, incluidos británicos, otros europeos y asiáticos centrales. Los costos oscilan entre $ 4,000 (£ 3,000) por peleador y $ 20,000 para una gran familia.

El luchador francés Abu Basir al-Faransy, un joven francés, se fue antes de que las cosas se pusieran realmente difíciles en Raqqa. Ahora está en Idlib, donde dice que quiere quedarse. Los combates en Raqqa fueron intensos, incluso en aquel entonces, dice. "Éramos luchadores de primera línea, librando guerras casi constantemente [contra los kurdos], viviendo una vida difícil.

No sabíamos que Raqqa estaba a punto de ser sitiada ".

Desilusionado, cansado de las peleas constantes y temiendo por su vida, Abu Basir decidió irse por la seguridad de Idlib. Ahora vive en la ciudad.

Formó parte de un grupo casi exclusivamente francés dentro de IS, y antes de irse, a algunos de sus compañeros de lucha se les dio una nueva misión.

Hay algunos hermanos franceses de nuestro grupo que partieron hacia Francia para llevar a cabo ataques. en lo que se llamaría un 'día de ajuste de cuentas' ". Mucho está escondido debajo de los escombros de Raqqa y las mentiras alrededor de este trato fácilmente podrían haber permanecido enterradas allí también.

Los números que salieron fueron mucho más altos que los ancianos tribales locales admitieron. Al principio, la coalición se negó a admitir el alcance del trato.

Las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias lideradas por los kurdos, de alguna manera improbable, continúan sosteniendo que no se llegó a ningún acuerdo. Y es posible que ni siquiera se tratara de liberar a los rehenes civiles.

En lo que respecta a la coalición, no hubo transferencia de rehenes de IS a manos de la coalición o SDF. Y a pesar de las negativas de la coalición, decenas de combatientes extranjeros, según testigos presenciales, se unieron al éxodo.

El acuerdo para liberar a IS era mantener buenas relaciones entre los kurdos que lideran la lucha y las comunidades árabes que los rodean. También se trataba de minimizar las bajas. IS fue excavado en el hospital y el estadio de la ciudad. Cualquier esfuerzo para desalojarlo habría sido sangriento y prolongado.

La guerra contra IS tiene un doble propósito: primero destruir el llamado califato retomando territorio y segundo, prevenir ataques terroristas en el mundo más allá de Siria e Irak.

Raqqa era efectivamente la capital del Estado Islámico, pero también era una jaula: los combatientes quedaron atrapados allí.

El acuerdo para salvar a Raqqa puede haber valido la pena.

Pero también ha significado que militantes endurecidos en la batalla se han extendido por Siria y más allá, y muchos de ellos no "Ya terminé de pelear.

Todos los nombres de las personas que aparecen en el informe han cambiado.

Raqqa’s dirty secret

- Ver original

- noviembre 13º, 2017

Lorry driver Abu Fawzi thought it was going to be just another job.

He drives an 18-wheeler across some of the most dangerous territory in northern Syria. Bombed-out bridges, deep desert sand, even government forces and so-called Islamic State fighters don’t stand in the way of a delivery.

But this time, his load was to be human cargo. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an alliance of Kurdish and Arab fighters opposed to IS, wanted him to lead a convoy that would take hundreds of families displaced by fighting from the town of Tabqa on the Euphrates river to a camp further north.

The job would take six hours, maximum – or at least that's what he was told.

But when he and his fellow drivers assembled their convoy early on 12 October, they realised they had been lied to.

Instead, it would take three days of hard driving, carrying a deadly cargo - hundreds of IS fighters, their families and tonnes of weapons and ammunition.

Abu Fawzi and dozens of other drivers were promised thousands of dollars for the task but it had to remain secret.

The deal to let IS fighters escape from Raqqa – de facto capital of their self-declared caliphate – had been arranged by local officials. It came after four months of fighting that left the city obliterated and almost devoid of people. It would spare lives and bring fighting to an end. The lives of the Arab, Kurdish and other fighters opposing IS would be spared.

But it also enabled many hundreds of IS fighters to escape from the city. At the time, neither the US and British-led coalition, nor the SDF, which it backs, wanted to admit their part.

Has the pact, which stood as Raqqa’s dirty secret, unleashed a threat to the outside world - one that has enabled militants to spread far and wide across Syria and beyond?

Great pains were taken to hide it from the world. But the BBC has spoken to dozens of people who were either on the convoy, or observed it, and to the men who negotiated the deal.

In a greasy yard in Tabqa, underneath a date palm, three boys are busy at work rebuilding a lorry engine. They are covered in motor oil. Their hair, black and oily, stands on end.

Near them is a group of drivers. Abu Fawzi is at the centre, conspicuous in his bright red jacket. It matches the colour of his beloved 18-wheeler. He’s clearly the leader, quick to offer tea and cigarettes. At first he says he doesn’t want to speak but soon changes his mind.

He and the rest of the drivers are angry. It’s weeks since they risked their lives for a journey that ruined engines and broke axles but still they haven’t been paid. It was a journey to hell and back, he says.

“We were scared from the moment we entered Raqqa,” he says. “We were supposed to go in with the SDF, but we went alone. As soon as we entered, we saw IS fighters with their weapons and suicide belts on. They booby-trapped our trucks. If something were to go wrong in the deal, they would bomb the entire convoy. Even their children and women had suicide belts on.”

The Kurdish-led SDF cleared Raqqa of media. Islamic State’s escape from its base would not be televised.

Publicly, the SDF said that only a few dozen fighters had been able to leave, all of them locals.

But one lorry driver tells us that isn't true.

Another driver says the convoy was six to seven kilometres long. It included almost 50 trucks, 13 buses and more than 100 of the Islamic State group’s own vehicles. IS fighters, their faces covered, sat defiantly on top of some of the vehicles.

Footage secretly filmed and passed to us shows lorries towing trailers crammed with armed men. Despite an agreement to take only personal weapons, IS fighters took everything they could carry. Ten trucks were loaded with weapons and ammunition.

The drivers point to a white truck being worked on in the corner of the yard. “Its axle was broken because of the weight of the ammo,” says Abu Fawzi.

This wasn’t so much an evacuation - it was the exodus of so-called Islamic State.

The SDF didn’t want the retreat from Raqqa to look like an escape to victory. No flags or banners would be allowed to be flown from the convoy as it left the city, the deal stipulated.

It was also understood that no foreigners would be allowed to leave Raqqa alive.

Back in May, US Defence Secretary James Mattis described the fight against IS as a war of “annihilation”.“Our intention is that the foreign fighters do not survive the fight to return home to north Africa, to Europe, to America, to Asia, to Africa. We are not going to allow them to do so,” he said on US television.

But foreign fighters – those not from Syria and Iraq - were also able to join the convoy, according to the drivers. One explains:

Other drivers chipped in with the names of different nationalities.

In light of the BBC investigation, the coalition now admits the part it played in the deal. Some 250 IS fighters were allowed to leave Raqqa, with 3,500 of their family members.

“We didn’t want anyone to leave,” says Col Ryan Dillon, spokesman for Operation Inherent Resolve, the Western coalition against IS.

“But this goes to the heart of our strategy, ‘by, with and through’ local leaders on the ground. It comes down to Syrians – they are the ones fighting and dying, they get to make the decisions regarding operations,” he says.

While a Western officer was present for the negotiations, they didn’t take an “active part” in the discussions. Col Dillon maintains, though, that only four foreign fighters left and they are now in SDF custody.

As it left the city, the convoy would pass through the well-irrigated cotton and wheat fields north of Raqqa. Small villages gave way to desert. The convoy left the main road and took to tracks across the desert. The trucks found it hard going, but it was much harder for the men behind the wheel.

A friend of Abu Fawzi's rolls up the sleeve of his tunic. Underneath, there are burns on his skin. “Look what they did here,” he says.

According to Abu Fawzi, there were three or four foreigners with each driver. They would beat him and call him names, such as “infidel”, or “pig”.

They might have been helping the fighters escape, but the Arab drivers were abused the entire route, they say. And threatened.

“They said, 'Let us know when you rebuild Raqqa - we will come back,’” says Abu Fawzi. “They were defiant and didn’t care. They accused us of kicking them out of Raqqa.”

A female foreign fighter threatened him with her AK-47.

Shopkeeper Mahmoud doesn’t get intimidated by much.

It was about four in the afternoon when an SDF convoy drove through his town, Shanine, and everyone was told to go indoors.

“We were here and an SDF vehicle stopped by to say there was a truce agreement between them and IS,” he says. “They wanted us to clear the area.”

He is no fan of IS, but he couldn’t miss a business opportunity - even if some of the 4,000 surprise customers driving through his village were armed to the teeth.

A small bridge in the village created a bottleneck so the IS fighters got out and went shopping. After months of fighting and taking cover in bunkers, they were pale and hungry. They filed into his shop and, he says, they cleared his shelves.

“A one-eyed Tunisian fighter told me to fear God,” he says. “In a very calm voice, he asked why I had shaved. He said they would come back and enforce Sharia once again. I told him we have no problem with Sharia laws. We're all Muslims.”

Instant noodles, biscuits and snacks - they bought everything they could get their hands on.

They left their weapons outside the shop. The only trouble he had was when three of the fighters spied some cigarettes – contraband in their eyes – and tore up the boxes.

“They didn't appropriate anything, nothing at all,” he says.

“Only three of them went rogue. Other IS fighters even chastised them.”

He says IS paid for what they took.

“They hoovered up the shop. I got overwhelmed by their numbers. Many asked me for prices, but I couldn't answer them because I was busy serving other people. So they left money for me on my desk without me asking.”

Despite the abuse they suffered, the lorry drivers agreed - when it came to money, IS settled its bills.

Says Abu Fawzi with a smile.

North of the village, it’s a different landscape. A lonely tractor ploughs a field, sending a plume of dust and sand into the air that can be seen for miles. There are fewer villages, and it’s here that the convoy sought to disappear.

In Muhanad’s tiny village, people fled as the convoy approached, fearing for their homes - and their lives.

But suddenly, the vehicles turned right, leaving the main road for a desert track.

“Two Humvees were leading the convoy ahead,” says Muhanad. “They were organising it and wouldn't let anyone pass them.”

As the convoy disappeared into the haze of the desert, Muhanad felt no immediate relief. Almost everyone we spoke to says IS threatened to return, its fighters running a finger across their throats as they passed by.

“We've been living in terror for the past four or five years,” says Muhanad.

Along the route, many people we spoke to said they heard coalition aircraft, sometimes drones, following the convoy.

From the cab of his truck, Abu Fawzi watched as a coalition warplane flew overhead, dropping illumination flares, which lit up the convoy and the road ahead.

The coalition now confirms that while it did not have its personnel on the ground, it monitored the convoy from the air.

Past the last SDF checkpoint, inside IS territory - a village between Markada and Al-Souwar - Abu Fawzi reached his destination. His lorry was full of ammunition and IS fighters wanted it hidden.

When he finally made it back to safety, he was asked by the SDF where he’d dumped the goods.

“We showed them the location on the map and he marked it so uncle Trump can bomb it later,” he says.

Raqqa’s freedom was bought with blood, sacrifice and compromise. The deal freed its trapped civilians and ended the fight for the city. No SDF forces would have to die storming the last IS hideout.

But IS didn’t stay put for long. Freed from Raqqa, where they were surrounded, some of the group's most-wanted members have now spread far and wide across Syria and beyond.

The men who cut fences, climb walls and run through the tunnels out of Syria are reporting a big increase in people fleeing. The collapse of the caliphate is good for business.

“In the past couple of weeks, we’ve had lots of families leaving Raqqa and wanting to leave for Turkey. This week alone, I personally oversaw the smuggling of 20 families,” says Imad, a smuggler on the Turkish-Syrian border.

“Most were foreign but there were Syrians as well.”

He now charges $600 (£460) per person and a minimum of $1,500 for a family.

In this business, clients don’t take kindly to inquiries. But Imad says he’s had “French, Europeans, Chechens, Uzbek”.

“Some were talking in French, others in English, others in some foreign language,” he says.

Walid, another smuggler on a different stretch of the Turkish border, tells the same story.

“We had an influx of families over the past few weeks,” he says. “There were some large families crossing. Our job is to smuggle them through. We've had a lot of foreign families using our services.”

As Turkey has increased border security, the work has become more difficult.

However, Walid says it’s a different situation for senior IS figures.

“Those highly placed foreigners have their own networks of smugglers. It’s usually the same people who organised their access to Syria. They co-ordinate with one another.”

Smuggling didn’t work out for everyone. Abu Musab Huthaifa was one of Raqqa’s most notorious figures. The IS intelligence chief was on the convoy out of the city on 12 October.

But now he is behind bars, and his story reflects the final days of the crumbling caliphate.

Islamic State never negotiates. Uncompromising, murderous - this is an enemy that plays by a different set of rules.

At least that’s how the myth goes.

But in Raqqa, it behaved no differently from any other losing side. Cornered, exhausted and fearful for their families, IS fighters were bombed to the negotiating table on 10 October.

“Air strikes put pressure on us for almost 10 hours. They killed about 500 or 600 people, fighters and families,” says Abu Musab Huthaifa.

Footage of the coalition air strike that hit one neighbourhood of Raqqa on 11 October shows a human catastrophe behind enemy lines. Amid the screams of the women and children, there is chaos among the IS fighters. The bombs appear especially powerful, especially effective. Activists claim that a building housing 35 women and children was destroyed. It was enough to break their resistance.

Contains distressing material

“After 10 hours, negotiations kicked off again. Those who initially rejected the truce changed their minds. And thus we left Raqqa,” says Abu Musab.

There had been three previous attempts to negotiate a peace deal. A team of four, including local Raqqa officials, now led the talks. One brave soul would cross the front lines on his motorbike relaying messages.

“We were only to leave with our personal weapons and leave all heavy weapons behind. But we didn't have heavy weapons anyway,” Abu Musab says.

Now in jail on the Turkish-Syrian border, he has revealed details of what happened to the convoy when it made it safely to IS territory.

He says the convoy went to the countryside of eastern Syria, not far from the border with Iraq.

Thousands escaped, he says.

Abu Musab’s own attempted escape serves as a warning to the West of the threat from those freed from Raqqa.

How could one of the most notorious of IS chiefs escape through enemy territory and almost evade capture?

“I remained with a group which had set its mind on making its way to Turkey,” Abu Musab says.

Islamic State members were wanted by everyone else outside the group’s shrinking area of control; that meant this small gathering had to pass through swathes of hostile territory.

“We hired a smuggler to navigate us out of SDF-controlled areas,” Abu Musab says.

At first it went well. But smugglers are an unreliable lot. “He abandoned us midway. We were left to fend for ourselves in the midst of SDF areas. From then on, we disbanded and it was every man for himself,” says Abu Musab.

He might have made it to safety if only he’d paid the right person or maybe taken a different route.

The other path is to Idlib, to the west of Raqqa. Countless IS fighters and their families have found a haven there. Foreigners, too, also make it out - including Britons, other Europeans and Central Asians. The costs range from $4,000 (£3,000) per fighter to $20,000 for a large family.

Abu Basir al-Faransy, a young Frenchman, left before the going got really tough in Raqqa. He’s now in Idlib, where he says he wants to stay.

The fighting in Raqqa was intense, even back then, he says.

“We were front-line fighters, waging war almost constantly [against the Kurds], living a hard life. We didn't know Raqqa was about to be besieged.”

Disillusioned, weary of the constant fighting and fearing for his life, Abu Basir decided to leave for the safety of Idlib. He now lives in the city.

He was part of an almost exclusively French group within IS, and before he left some of his fellow fighters were given a new mission.

Much is hidden beneath the rubble of Raqqa and the lies around this deal might easily have stayed buried there too.

The numbers leaving were much higher than local tribal elders admitted. At first the coalition refused to admit the extent of the deal.

The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, somewhat improbably, continue to maintain that no deal was done.

And this may not even have been about freeing civilian hostages. As far as the coalition is concerned, there was no transfer of hostages from IS to coalition or SDF hands.

And despite coalition denials, dozens of foreign fighters, according to eyewitnesses, joined the exodus.

The deal to free IS was about maintaining good relations between the Kurds leading the fight and the Arab communities who surround them.

It was also about minimising casualties. IS was well dug in at the city’s hospital and stadium. Any effort to dislodge it head-on would have been bloody and prolonged.

The war against IS has a twin purpose: first to destroy the so-called caliphate by retaking territory and second, to prevent terror attacks in the world beyond Syria and Iraq.

Raqqa was effectively IS’s capital but it was also a cage - fighters were trapped there.

The deal to save Raqqa may have been worth it.

But it has also meant battle-hardened militants have spread across Syria and further afield – and many of them aren’t done fighting yet.

All names of the people featured in the report have been changed.

One of the drivers maps out the route of the convoy

One of the drivers maps out the route of the convoy IS family members prepare to leave

IS family members prepare to leave Mahmoud's shop

Mahmoud's shop Abu Mus’ab

Abu Mus’abRaqqa’sdirty secret

By Quentin Sommerville and Riam Dalati

The BBC has uncovered details of a secret deal that let hundreds of IS fighters and their families escape from Raqqa, under the gaze of the US and British-led coalition and Kurdish-led forces who control the city.

A convoy included some of IS’s most notorious members and – despite reassurances – dozens of foreign fighters. Some of those have spread out across Syria, even making it as far as Turkey.

Lorry driver Abu Fawzi thought it was going to be just another job.

He drives an 18-wheeler across some of the most dangerous territory in northern Syria. Bombed-out bridges, deep desert sand, even government forces and so-called Islamic State fighters don’t stand in the way of a delivery.

But this time, his load was to be human cargo. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an alliance of Kurdish and Arab fighters opposed to IS, wanted him to lead a convoy that would take hundreds of families displaced by fighting from the town of Tabqa on the Euphrates river to a camp further north.

The job would take six hours, maximum – or at least that's what he was told.

But when he and his fellow drivers assembled their convoy early on 12 October, they realised they had been lied to.

Instead, it would take three days of hard driving, carrying a deadly cargo - hundreds of IS fighters, their families and tonnes of weapons and ammunition.

Abu Fawzi and dozens of other drivers were promised thousands of dollars for the task but it had to remain secret.

The deal to let IS fighters escape from Raqqa – de facto capital of their self-declared caliphate – had been arranged by local officials. It came after four months of fighting that left the city obliterated and almost devoid of people. It would spare lives and bring fighting to an end. The lives of the Arab, Kurdish and other fighters opposing IS would be spared.

But it also enabled many hundreds of IS fighters to escape from the city. At the time, neither the US and British-led coalition, nor the SDF, which it backs, wanted to admit their part.

Has the pact, which stood as Raqqa’s dirty secret, unleashed a threat to the outside world - one that has enabled militants to spread far and wide across Syria and beyond?

Great pains were taken to hide it from the world. But the BBC has spoken to dozens of people who were either on the convoy, or observed it, and to the men who negotiated the deal.

Out of the city

In a greasy yard in Tabqa, underneath a date palm, three boys are busy at work rebuilding a lorry engine. They are covered in motor oil. Their hair, black and oily, stands on end.

Near them is a group of drivers. Abu Fawzi is at the centre, conspicuous in his bright red jacket. It matches the colour of his beloved 18-wheeler. He’s clearly the leader, quick to offer tea and cigarettes. At first he says he doesn’t want to speak but soon changes his mind.

He and the rest of the drivers are angry. It’s weeks since they risked their lives for a journey that ruined engines and broke axles but still they haven’t been paid. It was a journey to hell and back, he says.

One of the drivers maps out the route of the convoy

“We were scared from the moment we entered Raqqa,” he says. “We were supposed to go in with the SDF, but we went alone. As soon as we entered, we saw IS fighters with their weapons and suicide belts on. They booby-trapped our trucks. If something were to go wrong in the deal, they would bomb the entire convoy. Even their children and women had suicide belts on.”

The Kurdish-led SDF cleared Raqqa of media. Islamic State’s escape from its base would not be televised.

Publicly, the SDF said that only a few dozen fighters had been able to leave, all of them locals.

But one lorry driver tells us that isn't true.

We took out around 4,000 people including women and children - our vehicle and their vehicles combined. When we entered Raqqa, we thought there were 200 people to collect. In my vehicle alone, I took 112 people.”

Another driver says the convoy was six to seven kilometres long. It included almost 50 trucks, 13 buses and more than 100 of the Islamic State group’s own vehicles. IS fighters, their faces covered, sat defiantly on top of some of the vehicles.

Footage secretly filmed and passed to us shows lorries towing trailers crammed with armed men. Despite an agreement to take only personal weapons, IS fighters took everything they could carry. Ten trucks were loaded with weapons and ammunition.

The drivers point to a white truck being worked on in the corner of the yard. “Its axle was broken because of the weight of the ammo,” says Abu Fawzi.

This wasn’t so much an evacuation - it was the exodus of so-called Islamic State.

The SDF didn’t want the retreat from Raqqa to look like an escape to victory. No flags or banners would be allowed to be flown from the convoy as it left the city, the deal stipulated.

It was also understood that no foreigners would be allowed to leave Raqqa alive.

Back in May, US Defence Secretary James Mattis described the fight against IS as a war of “annihilation”.“Our intention is that the foreign fighters do not survive the fight to return home to north Africa, to Europe, to America, to Asia, to Africa. We are not going to allow them to do so,” he said on US television.

But foreign fighters – those not from Syria and Iraq - were also able to join the convoy, according to the drivers. One explains:

There was a huge number of foreigners. France, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Yemen, Saudi, China, Tunisia, Egypt...”

Other drivers chipped in with the names of different nationalities.

In light of the BBC investigation, the coalition now admits the part it played in the deal. Some 250 IS fighters were allowed to leave Raqqa, with 3,500 of their family members.

“We didn’t want anyone to leave,” says Col Ryan Dillon, spokesman for Operation Inherent Resolve, the Western coalition against IS.

“But this goes to the heart of our strategy, ‘by, with and through’ local leaders on the ground. It comes down to Syrians – they are the ones fighting and dying, they get to make the decisions regarding operations,” he says.

While a Western officer was present for the negotiations, they didn’t take an “active part” in the discussions. Col Dillon maintains, though, that only four foreign fighters left and they are now in SDF custody.

IS family members prepare to leave

As it left the city, the convoy would pass through the well-irrigated cotton and wheat fields north of Raqqa. Small villages gave way to desert. The convoy left the main road and took to tracks across the desert. The trucks found it hard going, but it was much harder for the men behind the wheel.

A friend of Abu Fawzi's rolls up the sleeve of his tunic. Underneath, there are burns on his skin. “Look what they did here,” he says.

According to Abu Fawzi, there were three or four foreigners with each driver. They would beat him and call him names, such as “infidel”, or “pig”.

They might have been helping the fighters escape, but the Arab drivers were abused the entire route, they say. And threatened.

“They said, 'Let us know when you rebuild Raqqa - we will come back,’” says Abu Fawzi. “They were defiant and didn’t care. They accused us of kicking them out of Raqqa.”

A female foreign fighter threatened him with her AK-47.

Into the desert

Shopkeeper Mahmoud doesn’t get intimidated by much.

It was about four in the afternoon when an SDF convoy drove through his town, Shanine, and everyone was told to go indoors.

“We were here and an SDF vehicle stopped by to say there was a truce agreement between them and IS,” he says. “They wanted us to clear the area.”

He is no fan of IS, but he couldn’t miss a business opportunity - even if some of the 4,000 surprise customers driving through his village were armed to the teeth.

Mahmoud's shop

A small bridge in the village created a bottleneck so the IS fighters got out and went shopping. After months of fighting and taking cover in bunkers, they were pale and hungry. They filed into his shop and, he says, they cleared his shelves.

“A one-eyed Tunisian fighter told me to fear God,” he says. “In a very calm voice, he asked why I had shaved. He said they would come back and enforce Sharia once again. I told him we have no problem with Sharia laws. We're all Muslims.”

Instant noodles, biscuits and snacks - they bought everything they could get their hands on.

They left their weapons outside the shop. The only trouble he had was when three of the fighters spied some cigarettes – contraband in their eyes – and tore up the boxes.

“They didn't appropriate anything, nothing at all,” he says.

“Only three of them went rogue. Other IS fighters even chastised them.”

He says IS paid for what they took.

“They hoovered up the shop. I got overwhelmed by their numbers. Many asked me for prices, but I couldn't answer them because I was busy serving other people. So they left money for me on my desk without me asking.”

Despite the abuse they suffered, the lorry drivers agreed - when it came to money, IS settled its bills.

IS may have been homicidal psychopaths, but they're always correct with the money.”

Says Abu Fawzi with a smile.

North of the village, it’s a different landscape. A lonely tractor ploughs a field, sending a plume of dust and sand into the air that can be seen for miles. There are fewer villages, and it’s here that the convoy sought to disappear.

In Muhanad’s tiny village, people fled as the convoy approached, fearing for their homes - and their lives.

But suddenly, the vehicles turned right, leaving the main road for a desert track.

“Two Humvees were leading the convoy ahead,” says Muhanad. “They were organising it and wouldn't let anyone pass them.”

As the convoy disappeared into the haze of the desert, Muhanad felt no immediate relief. Almost everyone we spoke to says IS threatened to return, its fighters running a finger across their throats as they passed by.

“We've been living in terror for the past four or five years,” says Muhanad.

It will take us a while to rid ourselves of that psychological fear. We feel that they may be coming back for us, or will send sleeper agents. We’re still not sure that they've gone for good.”

Along the route, many people we spoke to said they heard coalition aircraft, sometimes drones, following the convoy.

From the cab of his truck, Abu Fawzi watched as a coalition warplane flew overhead, dropping illumination flares, which lit up the convoy and the road ahead.

When the last of the convoy were about to cross, a US jet flew very low and deployed flares to light up the area. IS fighters shat their pants.”

The coalition now confirms that while it did not have its personnel on the ground, it monitored the convoy from the air.

Past the last SDF checkpoint, inside IS territory - a village between Markada and Al-Souwar - Abu Fawzi reached his destination. His lorry was full of ammunition and IS fighters wanted it hidden.

When he finally made it back to safety, he was asked by the SDF where he’d dumped the goods.

“We showed them the location on the map and he marked it so uncle Trump can bomb it later,” he says.

Raqqa’s freedom was bought with blood, sacrifice and compromise. The deal freed its trapped civilians and ended the fight for the city. No SDF forces would have to die storming the last IS hideout.

But IS didn’t stay put for long. Freed from Raqqa, where they were surrounded, some of the group's most-wanted members have now spread far and wide across Syria and beyond.

The Smugglers

The men who cut fences, climb walls and run through the tunnels out of Syria are reporting a big increase in people fleeing. The collapse of the caliphate is good for business.

“In the past couple of weeks, we’ve had lots of families leaving Raqqa and wanting to leave for Turkey. This week alone, I personally oversaw the smuggling of 20 families,” says Imad, a smuggler on the Turkish-Syrian border.

“Most were foreign but there were Syrians as well.”

He now charges $600 (£460) per person and a minimum of $1,500 for a family.

In this business, clients don’t take kindly to inquiries. But Imad says he’s had “French, Europeans, Chechens, Uzbek”.

“Some were talking in French, others in English, others in some foreign language,” he says.

Walid, another smuggler on a different stretch of the Turkish border, tells the same story.

“We had an influx of families over the past few weeks,” he says. “There were some large families crossing. Our job is to smuggle them through. We've had a lot of foreign families using our services.”

As Turkey has increased border security, the work has become more difficult.

In some areas we’re using ladders, in others we cross through a river, in other areas we're using a steep mountainous trail. It’s a miserable situation.”

However, Walid says it’s a different situation for senior IS figures.

“Those highly placed foreigners have their own networks of smugglers. It’s usually the same people who organised their access to Syria. They co-ordinate with one another.”

Smuggling didn’t work out for everyone. Abu Musab Huthaifa was one of Raqqa’s most notorious figures. The IS intelligence chief was on the convoy out of the city on 12 October.

But now he is behind bars, and his story reflects the final days of the crumbling caliphate.

Islamic State never negotiates. Uncompromising, murderous - this is an enemy that plays by a different set of rules.

At least that’s how the myth goes.

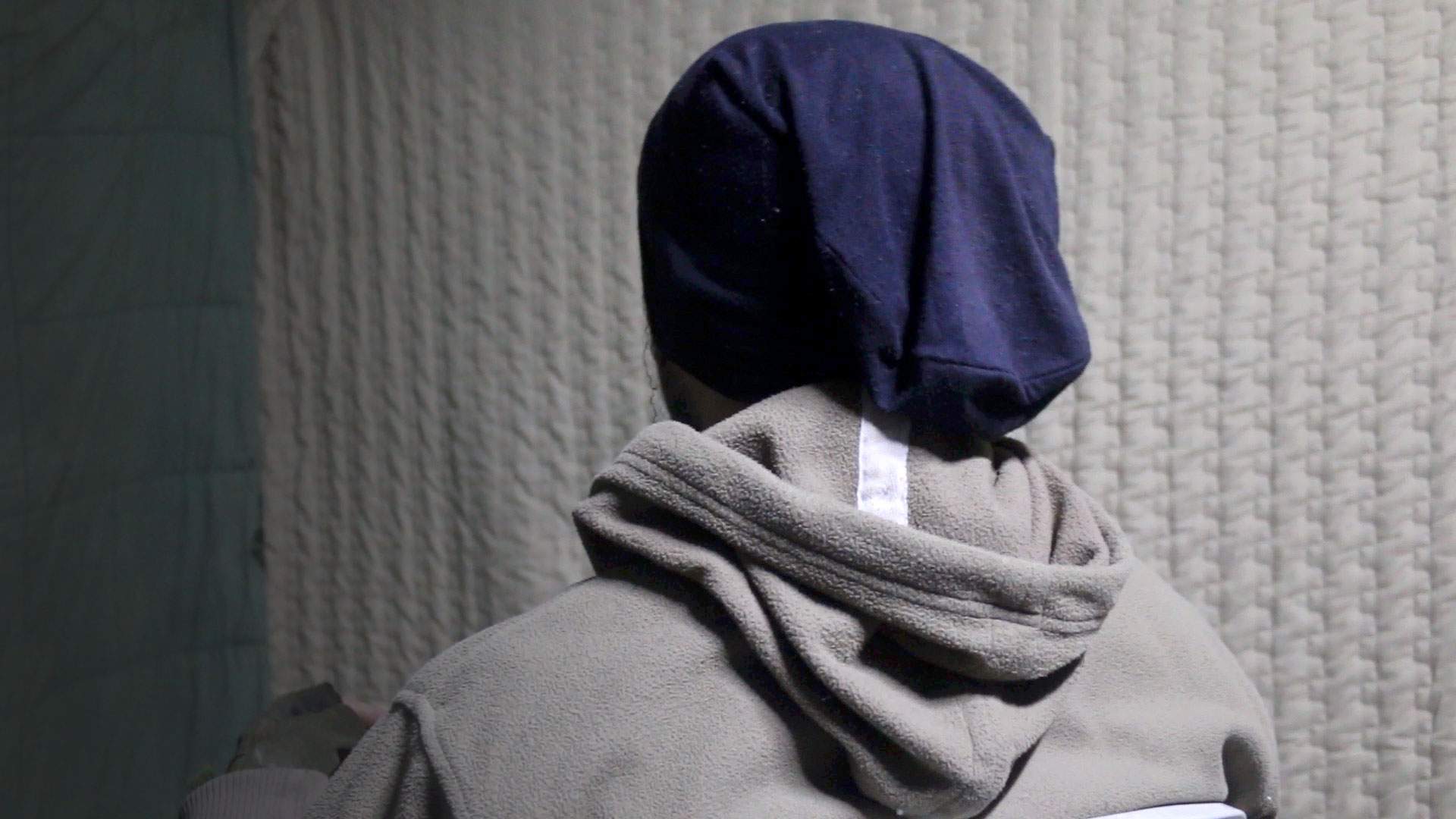

Abu Mus’ab

But in Raqqa, it behaved no differently from any other losing side. Cornered, exhausted and fearful for their families, IS fighters were bombed to the negotiating table on 10 October.

“Air strikes put pressure on us for almost 10 hours. They killed about 500 or 600 people, fighters and families,” says Abu Musab Huthaifa.

Footage of the coalition air strike that hit one neighbourhood of Raqqa on 11 October shows a human catastrophe behind enemy lines. Amid the screams of the women and children, there is chaos among the IS fighters. The bombs appear especially powerful, especially effective. Activists claim that a building housing 35 women and children was destroyed. It was enough to break their resistance.

Contains distressing material

“After 10 hours, negotiations kicked off again. Those who initially rejected the truce changed their minds. And thus we left Raqqa,” says Abu Musab.

There had been three previous attempts to negotiate a peace deal. A team of four, including local Raqqa officials, now led the talks. One brave soul would cross the front lines on his motorbike relaying messages.

“We were only to leave with our personal weapons and leave all heavy weapons behind. But we didn't have heavy weapons anyway,” Abu Musab says.

Now in jail on the Turkish-Syrian border, he has revealed details of what happened to the convoy when it made it safely to IS territory.

He says the convoy went to the countryside of eastern Syria, not far from the border with Iraq.

Thousands escaped, he says.

Abu Musab’s own attempted escape serves as a warning to the West of the threat from those freed from Raqqa.

How could one of the most notorious of IS chiefs escape through enemy territory and almost evade capture?

“I remained with a group which had set its mind on making its way to Turkey,” Abu Musab says.

Islamic State members were wanted by everyone else outside the group’s shrinking area of control; that meant this small gathering had to pass through swathes of hostile territory.

“We hired a smuggler to navigate us out of SDF-controlled areas,” Abu Musab says.

At first it went well. But smugglers are an unreliable lot. “He abandoned us midway. We were left to fend for ourselves in the midst of SDF areas. From then on, we disbanded and it was every man for himself,” says Abu Musab.

He might have made it to safety if only he’d paid the right person or maybe taken a different route.

The other path is to Idlib, to the west of Raqqa. Countless IS fighters and their families have found a haven there. Foreigners, too, also make it out - including Britons, other Europeans and Central Asians. The costs range from $4,000 (£3,000) per fighter to $20,000 for a large family.

French fighter

Abu Basir al-Faransy, a young Frenchman, left before the going got really tough in Raqqa. He’s now in Idlib, where he says he wants to stay.

The fighting in Raqqa was intense, even back then, he says.

“We were front-line fighters, waging war almost constantly [against the Kurds], living a hard life. We didn't know Raqqa was about to be besieged.”

Disillusioned, weary of the constant fighting and fearing for his life, Abu Basir decided to leave for the safety of Idlib. He now lives in the city.

He was part of an almost exclusively French group within IS, and before he left some of his fellow fighters were given a new mission.

There are some French brothers from our group who left for France to carry out attacks in what would be called a ‘day of reckoning.’”

Much is hidden beneath the rubble of Raqqa and the lies around this deal might easily have stayed buried there too.

The numbers leaving were much higher than local tribal elders admitted. At first the coalition refused to admit the extent of the deal.

The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, somewhat improbably, continue to maintain that no deal was done.

And this may not even have been about freeing civilian hostages. As far as the coalition is concerned, there was no transfer of hostages from IS to coalition or SDF hands.

And despite coalition denials, dozens of foreign fighters, according to eyewitnesses, joined the exodus.

The deal to free IS was about maintaining good relations between the Kurds leading the fight and the Arab communities who surround them.

It was also about minimising casualties. IS was well dug in at the city’s hospital and stadium. Any effort to dislodge it head-on would have been bloody and prolonged.

The war against IS has a twin purpose: first to destroy the so-called caliphate by retaking territory and second, to prevent terror attacks in the world beyond Syria and Iraq.

Raqqa was effectively IS’s capital but it was also a cage - fighters were trapped there.

The deal to save Raqqa may have been worth it.

But it has also meant battle-hardened militants have spread across Syria and further afield – and many of them aren’t done fighting yet.

All names of the people featured in the report have been changed.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario